Observing Coronavirus Pandemic with Raku

Every few years a new unknown virus pops up and starts spreading around the globe. This year, the situation with COVID-19 is different not only because of the nature of the virus but also because of the Internet. Whilst we have instant access to new information (which is often alarmist in tone) we also have the ability to access data for ourselves.

Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering synthesizes COVID-19 data from different sources, and displays it on their online dashboard. They also publish daily updates in CSV files on GitHub.

I decided to ingest their CSV data and display it using different visualizations to reduce panic and provide a way to quickly see real numbers and trends. The result is the website covid.observer. The source files are available in the GitHub repository.

For years Perl has been known for BioPerl. Let’s see what Raku can bring to society as its great at manipulating text data. The heart of the site is a Raku program and a few modules that parse data and create static HTML pages.

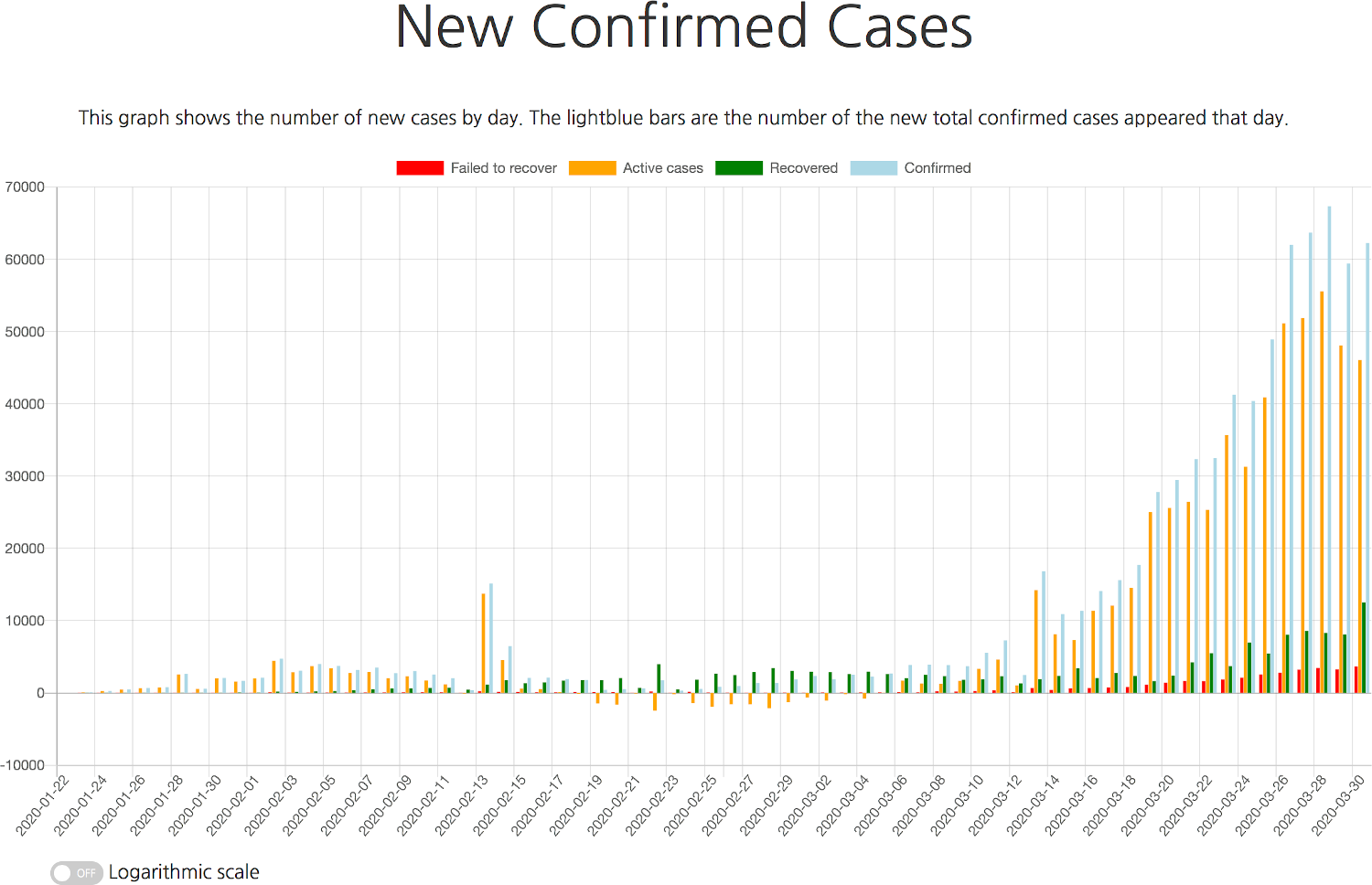

\

I’m going to show you a few of the most useful features that Raku offers to developers.

The MAIN function

The program works in three modes: parsing population data, getting updates from the COVID raw data, and generating HTML files. Raku gives us a very handy way to process command line arguments by defining different variants of the MAIN function. Each variant is mapped to different command line parameters, and Raku automatically dispatches to the matched variant, which helps me to run the program in the desired mode.

Here are the variants:

multi sub MAIN('population') {

. . .

}

multi sub MAIN('fetch') {

. . .

}

multi sub MAIN('generate') {

. . .

}

We don’t need to parse the command-line options ourselves, nor use any modules such as Getopt::Long to do it for us. Moreover, Raku emits “usage” help text if the program is run with incorrect or missing arguments:

$ ./covid.raku

Usage:

./covid.raku population

./covid.raku fetch

./covid.raku generate

Salve J. Nilsen proposed to add another MAIN function that prints the SQL commands for initializing the database. This example shows how how to define Boolean flags for command line options:

multi sub MAIN('setup', Bool :$force=False, Bool :$verbose=False) {

. . .

}

Note the : before the parameter name. We’ll see it again later.

An additional POD comment can be added before each version of the function to print a better usage description, for example:

#| Fetch the latest data and rebuild the database

multi sub MAIN('fetch') {

. . .

}

Now the program prints a more helpful usage message:

Usage:

./covid.raku population -- Parse population CSV files

./covid.raku fetch -- Fetch the latest data and rebuild the database

./covid.raku generate -- Generate the website

Reduction operators

Reduction operators are really useful. Let me remind you what a reduction operator is. It’s actually a meta-operator: an infix operator surrounded by square brackets.

In the program the reduction operator is widely used for computing totals across the data sets (e.g. for the World, or across Chinese provinces). Let us examine a few cases of increasing complexity:

First there’s a simple hash, and we need to add up its values:

my %data =

IT => 59_138,

CN => 81_397,

ES => 28_768;

my $total = [+] %data.values;

say $total; # 169303

This is the classic use case for the reduction operator. What I noticed during the work is that the [-] construct helps when you need to reduce some value by a few other values:

my %data =

confirmed => 100,

failed => 1,

recovered => 70;

my $active = [-] %data<confirmed recovered failed>;

say "$active active cases";

Using a hash slice in the form of %h<a b c> also helps to make the code more compact. Compare this with the straightforward approach:

my $active = %data<confirmed> - %data<failed> - %data<recovered>;

Filtering data

For our second case, the hash values are not scalars but hashes themselves. The >> hyperoperator can be used to extract deeply located data. Let me demonstrate this on a simplified data fragment:

my %data =

IT => {

confirmed => 59_138,

population => 61, # millions

},

CN => {

confirmed => 81_397,

population => 1434

},

ES => {

confirmed => 28_768,

population => 47,

};

my $total = [+] %data.values>><confirmed>;

say $total; # 169303

An alternative and cleaner way is using the map method to access the data:

my $total2 = [+] %data.values.map: *<confirmed>;

say $total2; # 169303

Finally, to exclude a country from the results, you can grep the keys in-place:

my %x = %data.grep: *.key ne 'CN';

my $excl2 = [+] %x.values.map: *<confirmed>;

say $excl2; # 87906

Notice that calling the hash’s grep method is much handier than trying to loop over the keys and filter them:

my $excluding-china =

[+] %data{%data.keys.grep: * ne 'CN'}.values.map: *<confirmed>;

say $excluding-china; # 87906

Hyper operators

In the previous section I showed how to apply the same action to each element of a list using >>. Now let us take a look at a real example of how I used the hyper operator >>->> to compute the deltas of number series:

my @confirmed = 10, 20, 40, 70, 150;

my @delta = @confirmed[1..*] >>->> @confirmed;

say @delta; # [10 20 30 80]

The array contains a series of values for the given period of time. The task is to compute how many new cases happen in each day. Instead of using a loop, it is possible to simply ‘subtract‘ an array from itself but shifted by one element.

The >>->> operator takes two data series: the slice @confirmed[1..*] of the original data without the first element, and the original @confirmed array. For a given binary operator (- in this example), you can construct four hyper operators: >>-<<, >>->>, <<->>, <<-<<. The chosen form allows us to ignore the extra item at the end of @confirmed when it is applied against @confirmed[1..*].

Junctions

Let me demonstrate a way of using the junction operator | which I discovered recently. It chooses the ending for the given ordinal number:

for 1..31 -> $day {

my $ending = do given $day {

when 1|21|31 {'st'}

when 2|22 {'nd'}

when 3|23 {'rd'}

default {'th'}

}

say "$day$ending";

}

The when blocks catch the corresponding numbers that need special endings. Junctions such as 1|21|31 are more elegant than a regular expression or a chain of comparisons.

Optional and named parameters

Parameter processing is simple in Raku. This function accepts two positional hash parameters:

sub chart-daily(%countries, %totals) {

. . .

}

I can easily add optional named parameters:

sub chart-daily(%countries, %totals, :$cc?, :$cont?, :$exclude?) {

. . .

}

A colon before the name makes the parameter named, and the question mark makes it optional. I am using this to modify the behavior of the same statistical function for aggregating data over the whole World, the continents, or to exclude a single country or a region:

Generating data for the whole World:

chart-daily(%countries, %per-day);

For a single country:

my $cc = 'CN';

chart-daily(%countries, %per-day, :$cc);

For a continent:

my $cont = 'Europe';

chart-daily(%countries, %per-day, :$cont);

World data excluding China:

chart-daily(%countries, %per-day, exclude => 'CN');

Getting data for China without its most affected province:

chart-daily(%countries, %per-day, cc => 'CN', exclude => 'CN/HB');

A built-in template engine

The project generates more than 200 HTML files, so templating is an important part of it. Fortunately Raku has a great out-of-the-box templating mechanism, which is much more powerful than simple variable interpolation.

A minimal example is substituting variables:

return qq:to/HTML/;

<div id="countries-list">

$html

</div>

HTML

By the way, notice that Raku lets you keep the indentation of a multi-line string by simply indenting its closing symbol. No extra spaces at the beginning of the lines will appear in the result.

A more exciting thing is that you can embed Raku code blocks into strings, and those blocks can contain any logic you need to make a right decision somewhere in the middle of the template:

my $content = qq:to/HTML/;

<h1>Coronavirus in {$country-name}</h1>

<div class="affected">

{

if $chart2data<confirmed> {

'Affected 1 of every ' ~

fmtnum((1_000_000 * $population /

$chart2data<confirmed>).round())

}

else {

'Nobody affected'

}

}

</div>

HTML

Here, the string builds itself depending on data. For each generated country, the string ’chooses‘ which phrase to embed and how to format the number. The if block is a relatively big chunk of Raku code that generates a string, which is used in place of the whole block in curly braces. Thus, inside this embedded code block you can freely manipulate data from the outside code.

Afterword

I must say that it is quite exciting to use Raku for a real project. As you can see from the examples, many of its ‘strange‘ features demonstrate how useful they are in different circumstances. Examine the code in the GitHub repository and follow the updates about the site on my blog.

Tags

Andrew Shitov

Andrew is a Perl 6 and Raku enthusiast since around 2000, an author of a number of books, and the organiser or a lot of Perl and Raku events, including three annual European conferences. Currently working on his new book Creating a Compiler with Raku.

Browse their articles

Feedback

Something wrong with this article? Help us out by opening an issue or pull request on GitHub